What happens to the money if the child turns adulthood—can the trust delay access or set conditions? – North Carolina

Short Answer

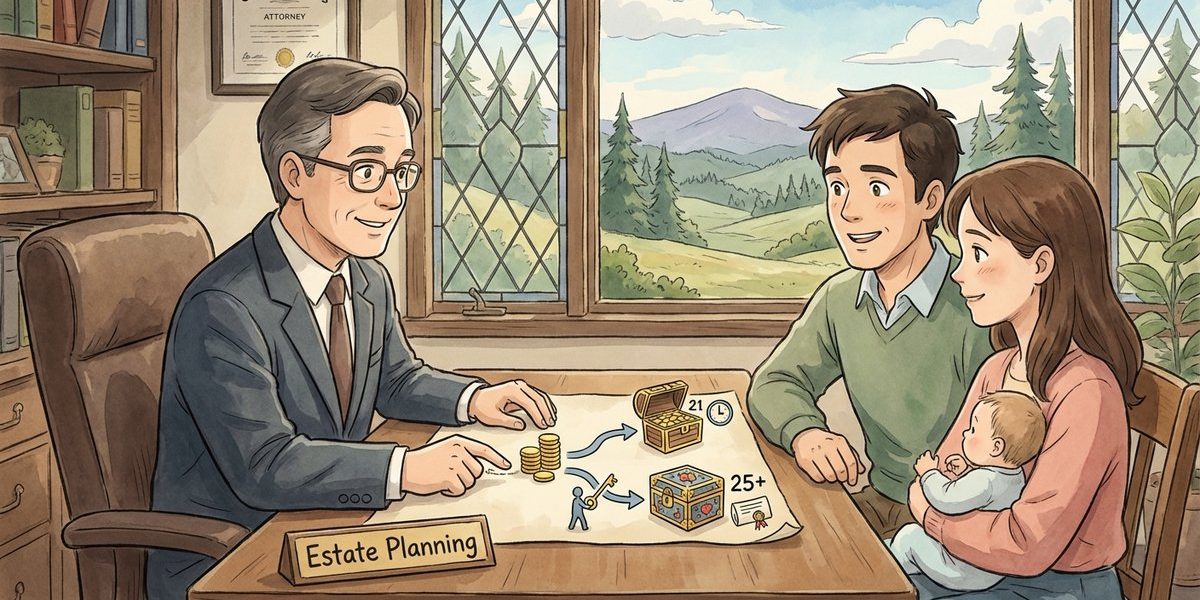

In North Carolina, an irrevocable third-party trust can be drafted to delay a beneficiary’s access past age 18 and to set conditions for distributions, as long as the terms are clear and lawful. By contrast, a UTMA custodial account generally must be turned over to the beneficiary at 18 or 21 (depending on how it was set up), and a custodial trust can allow the beneficiary to direct distributions once not incapacitated. The right tool depends on whether the goal is “access at adulthood” or “access only when certain milestones are met.”

Understanding the Problem

In North Carolina estate planning, the decision point is whether a minor beneficiary should receive full control of money automatically at adulthood, or whether a trustee should be allowed to hold the money longer and make distributions only under stated rules. The typical setup involves a third-party (non-parent) funded arrangement where an adult trustee holds and invests the funds for the child’s benefit while the child is a minor, and then the question becomes what happens when the child reaches age 18. The issue often comes up when ongoing contributions are planned and the beneficiary lives in a different jurisdiction than the person funding the arrangement.

Apply the Law

North Carolina generally allows a properly drafted trust to control when and how a beneficiary receives trust property. With an irrevocable third-party trust, the trust document can set a distribution age (for example, 25 or 30), stagger distributions (for example, one-third at 25, one-third at 30, balance at 35), or require conditions (for example, completing education, maintaining employment, or meeting other objective standards). The trustee then follows the trust’s instructions and uses the discretion (if any) granted by the trust. If the arrangement is instead a custodial account under the North Carolina Uniform Transfers to Minors Act (UTMA), the law generally requires turnover to the beneficiary at a statutory age, which limits the ability to delay access.

Key Requirements

- Choose the right vehicle: A third-party irrevocable trust can be designed to delay access and set conditions; a UTMA account is designed to end at a set age and then transfer outright.

- Clear distribution terms: The trust should state whether distributions are mandatory at a certain age, staggered, or discretionary, and what standards (health, education, support, maintenance, or other conditions) apply.

- Trustee authority and guardrails: The document should spell out who serves as trustee, what discretion the trustee has, and what happens if the beneficiary demands money at adulthood.

What the Statutes Say

- N.C. Gen. Stat. § 33A-20 (Termination of custodianship) – UTMA custodial property must generally be transferred to the beneficiary at age 21 for many transfers, with an option to designate an age between 18 and 21 in certain cases, and at age 18 for certain other transfers.

- N.C. Gen. Stat. § 33B-9 (Use of custodial trust property) – In a custodial trust, the custodial trustee generally must pay or expend property as directed by a beneficiary who is not incapacitated.

- N.C. Gen. Stat. § 33B-2 (Custodial trust; general) – Establishes custodial trusts and notes that other non-custodial trusts can be created and enforced according to their terms.

Analysis

Apply the Rule to the Facts: The goal described is a third-party irrevocable trust (or similar arrangement) funded with recurring contributions for a minor beneficiary, with access at adulthood. If the arrangement is a true third-party trust, the terms can be written so that the beneficiary receives control at 18, or later, or in stages—because the trustee’s job is to follow the trust’s distribution instructions. If the arrangement is instead set up as a UTMA custodial account, North Carolina law generally requires turning the property over at a statutory age, which limits any attempt to delay access beyond what the statute allows.

Process & Timing

- Who sets it up: The person funding the arrangement (the “grantor”/“settlor”). Where: Typically with a North Carolina attorney drafting the trust and a financial institution opening an account titled in the trustee’s name as trustee. What: A written trust agreement (and account-opening paperwork consistent with the trust). When: Before significant funds are contributed, so contributions are clearly treated as trust property.

- Funding and administration: Recurring contributions are made into the trust account(s). The trustee tracks contributions, invests under the trust’s standards, and makes distributions only as allowed by the trust (for example, for education or support while the beneficiary is a minor).

- At adulthood: If the trust says “distribute outright at 18,” the trustee typically winds down and distributes. If the trust says “hold until 25” or “staggered distributions,” the trustee continues managing and distributing under those terms. If a UTMA account was used instead, the custodian must transfer the property when the statutory termination age is reached under the setup.

Exceptions & Pitfalls

- Using the wrong tool: A UTMA account is often simple, but it can force an outright transfer at the statutory age even if the original intent was to delay access or require conditions.

- Vague “conditions”: Conditions that are unclear or hard to administer can lead to disputes and make the trustee’s job difficult. Objective, measurable standards usually work better than subjective rules.

- Cross-jurisdiction administration: When the beneficiary lives in a different jurisdiction, the trust should clearly state governing law and trustee powers, and the trustee should understand practical issues like delivering funds, verifying identity, and documenting distributions.

- Accidental beneficiary control: Some custodial-trust-style arrangements can allow a non-incapacitated beneficiary to direct distributions, which may defeat the goal of delaying access.

Conclusion

In North Carolina, a properly drafted irrevocable third-party trust can delay a beneficiary’s access beyond age 18 and can set lawful conditions for distributions, because the trustee must follow the trust’s written terms. A UTMA custodial account is different: it generally must be turned over at a statutory age (often 21, sometimes 18, and in some cases an elected age between 18 and 21). The next step is to choose the vehicle and put the distribution age/conditions in a written trust agreement before making recurring contributions.

Talk to a Estate Planning Attorney

If you’re dealing with setting up a trust for a minor and deciding whether access should happen at age 18 or be delayed with conditions, our firm has experienced attorneys who can help explain options and timelines under North Carolina law. Call us today at [919-341-7055].

Disclaimer: This article provides general information about North Carolina law based on the single question stated above. It is not legal advice for your specific situation and does not create an attorney-client relationship. Laws, procedures, and local practice can change and may vary by county. If you have a deadline, act promptly and speak with a licensed North Carolina attorney.