How long does a will contest usually take, and what are the major steps in the process? – North Carolina

Short Answer

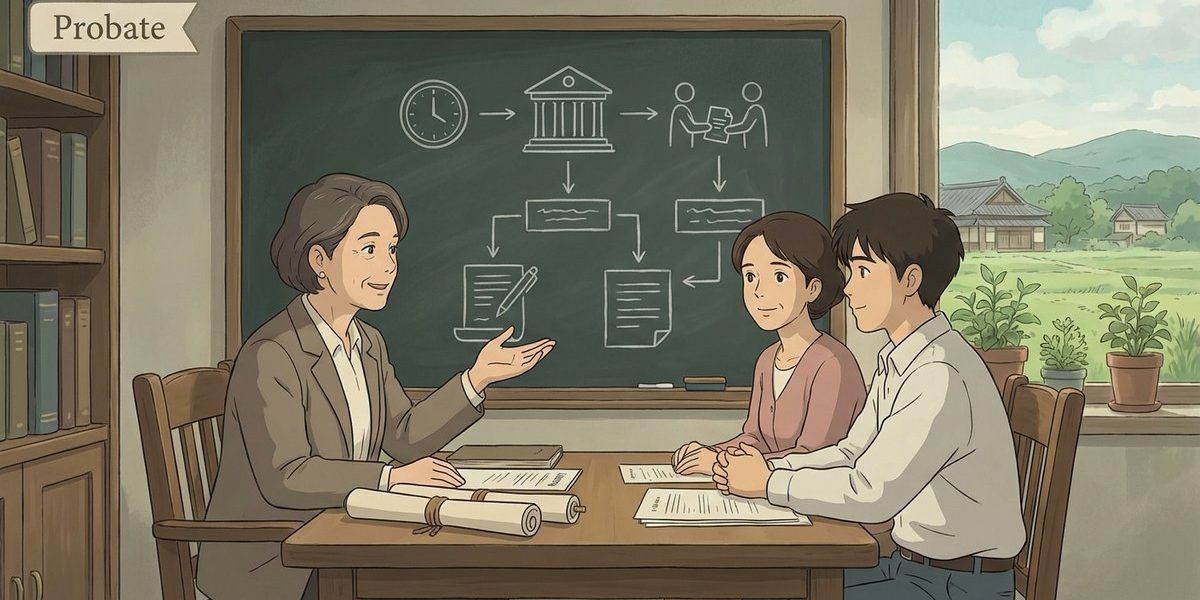

In North Carolina, a will contest (called a “caveat”) often takes months to more than a year, and sometimes longer, depending on how quickly the parties exchange information, whether the case settles, and the court’s trial calendar. The major steps usually include filing the caveat with the Clerk of Superior Court, serving all interested parties, an “alignment” hearing to set who is on each side, civil discovery, and then either settlement or a jury trial in Superior Court. A key deadline is that a caveat generally must be filed within three years after the will is probated in common form.

Understanding the Problem

In North Carolina probate, the core question is: how long does a will contest take once someone challenges a will after death, and what steps happen between filing the challenge and getting a final decision? The process matters because the estate administration can slow down while the dispute is pending, and the case can move from the Clerk of Superior Court to Superior Court for a jury trial. The timing often turns on when the will was admitted to probate, how many interested family members must be served, and how much factual investigation is needed about capacity and influence at the time the will was signed.

Apply the Law

North Carolina’s will contest procedure is typically started by filing a “caveat” in the decedent’s estate file with the Clerk of Superior Court. Once the caveat is filed, the law directs the clerk to transfer the case to Superior Court for a jury trial, and the caveator must serve all interested parties under the civil rules. While the caveat is pending, the clerk generally enters an order restricting distributions from the estate and setting rules for preserving assets and paying certain expenses, which can affect how quickly beneficiaries receive property.

Key Requirements

- Standing (an “interested party”): The person filing must have a direct financial interest in the estate that could be affected if the will is upheld or set aside.

- Timely filing: A caveat is generally allowed at probate or within three years after the will is probated in common form (with limited extensions for certain legal disabilities).

- Proper service and party alignment: After filing, the caveator must serve all interested parties, and the court holds an alignment hearing to determine who is aligned with the caveator (challenger) and who is aligned with the propounder (the side supporting the will).

What the Statutes Say

- N.C. Gen. Stat. § 31-32 (Filing of caveat) – Allows an interested party to file a caveat generally within three years after probate in common form, with limited extensions for certain disabilities.

- N.C. Gen. Stat. § 31-33 (Cause transferred to trial docket) – Requires transfer to Superior Court for a jury trial and sets service and alignment procedures.

- N.C. Gen. Stat. § 31-36 (Effect of caveat on estate administration) – Limits distributions during the caveat and outlines how the personal representative can preserve assets and pay certain expenses with notice and potential objections.

Analysis

Apply the Rule to the Facts: The facts describe a parent’s mental decline and a situation where an older child allegedly controlled access and communication, followed by a reported will change that excluded one child and benefited other relatives. In a North Carolina caveat, those facts commonly point to two central issues that drive both the steps and the timeline: whether the parent had testamentary capacity when the will was revised, and whether someone exerted undue influence over the parent at the time of signing. Because those issues usually require medical records, witness interviews, and depositions of the people involved in the will signing and caregiving, the case often takes longer than a simple probate administration.

Process & Timing

- Who files: An interested party (often a disinherited heir or prior beneficiary). Where: The Clerk of Superior Court in the county where the estate is opened (the decedent’s estate file). What: A caveat filed in the estate file; then service on all interested parties under the civil rules. When: Generally at probate or within three years after the will is probated in common form under North Carolina law.

- Transfer and alignment: After the caveat is filed, the clerk transfers the matter to Superior Court for a jury trial, and the court holds an alignment hearing so all interested parties can be placed on the challenger’s side or the will-supporting side (or dismissed but still bound). This step can take weeks to a few months depending on how quickly everyone is located and served.

- Discovery, motions, and resolution: The parties usually exchange documents and take depositions focused on the decedent’s condition at the time of signing, the circumstances of the will execution, and the beneficiary’s opportunity and motive to influence the decedent. Many cases resolve through settlement or mediation after key depositions; if not, the case proceeds to a jury trial in Superior Court, which can push the timeline out significantly based on the county’s trial calendar.

Exceptions & Pitfalls

- Waiting too long to file: The three-year caveat window can close even when family conflict or missing information delayed action, so checking the estate file early matters.

- Service and “missing party” problems: A caveat requires service on all interested parties. If addresses are outdated or family members are hard to locate, the case can stall and deadlines can be missed.

- Estate administration limits during the caveat: A caveat can restrict distributions while allowing certain expenses and claims to be handled with notice procedures, which can create practical pressure and disputes over what should be paid while the case is pending.

Conclusion

In North Carolina, a will contest is usually a caveat filed in the estate file with the Clerk of Superior Court, followed by service on all interested parties, an alignment hearing, civil discovery, and then settlement or a jury trial in Superior Court. The timeline commonly ranges from months to more than a year, depending on service issues, the amount of discovery needed, and the court’s schedule. The key threshold is filing by an interested party, and the key deadline is generally filing the caveat within three years after probate in common form.

Talk to a Probate Attorney

If you’re dealing with a disputed will after a parent’s death and need to understand the steps, timing, and what information matters most, our firm has experienced attorneys who can help you evaluate options and deadlines. Call us today at [919-341-7055].

Disclaimer: This article provides general information about North Carolina law based on the single question stated above. It is not legal advice for your specific situation and does not create an attorney-client relationship. Laws, procedures, and local practice can change and may vary by county. If you have a deadline, act promptly and speak with a licensed North Carolina attorney.