How does a balloon commercial real estate loan work, and what happens when the maturity date comes up? – North Carolina

Short Answer

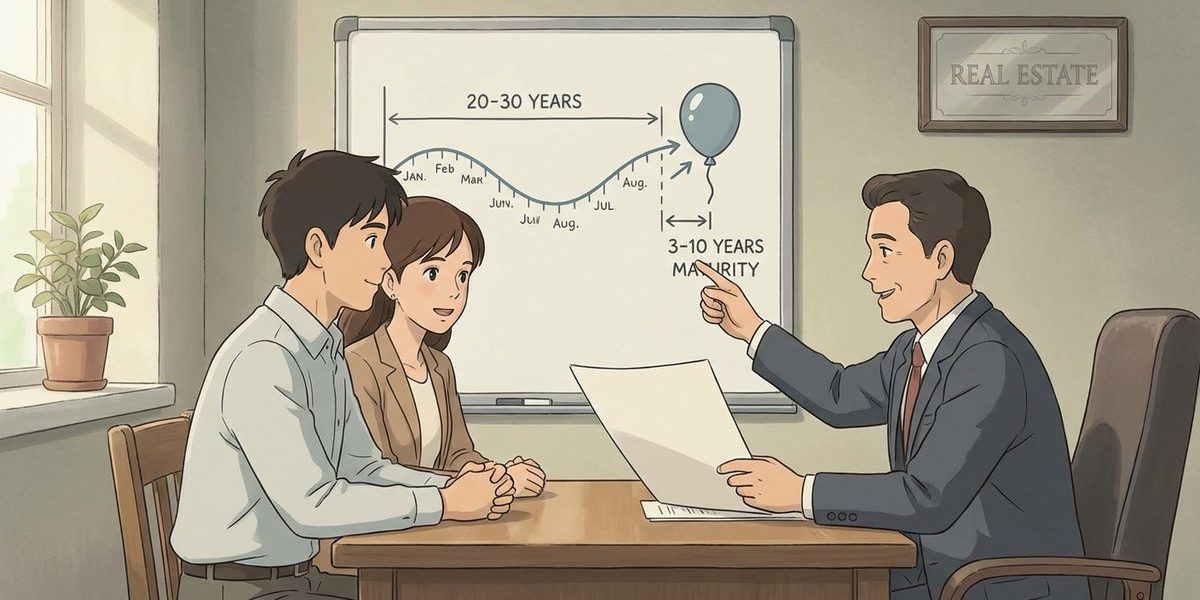

In North Carolina, a balloon commercial real estate loan usually has monthly payments calculated on a long amortization schedule (often 20–30 years), but the note “matures” earlier (often 3–10 years). When the maturity date arrives, the remaining principal balance typically becomes due in a lump sum unless the lender agrees to an extension, renewal, or modification. If the balance is not paid or extended, the loan can go into default and the lender may enforce its remedies under the note and deed of trust, which can include foreclosure.

Understanding the Problem

Under North Carolina commercial real estate lending, the key question is: when a bank loan is structured with a long amortization but a shorter balloon/maturity period, can the borrower keep making the same monthly payments after the maturity date, or must the remaining balance be paid off or refinanced? The decision point is what the loan documents require at maturity and what the lender will agree to at that time. This issue commonly comes up when a buyer plans to hold a building long-term but the bank’s initial term is shorter than the planned hold period.

Apply the Law

In a typical North Carolina balloon commercial loan, the promissory note controls the payment obligation and the maturity date, and the deed of trust secures the loan with a lien on the property. A “balloon” structure is usually not a separate legal category; it is a contract structure where the note requires a payoff at maturity even though the monthly payments were calculated as if the loan would run much longer. If the borrower does not pay the maturity balance and no extension is signed, the lender may treat that as a default and pursue the remedies stated in the loan documents, which often include acceleration and foreclosure under the deed of trust.

Key Requirements

- A stated maturity date and payoff obligation: The note typically states a specific date when all remaining sums are due, even if the monthly payment amount looks like a 20–30 year payment.

- A lender-approved “takeout” plan: If the borrower cannot pay the balloon from cash, the practical solution is usually refinancing, sale of the property, or a negotiated extension/renewal (often with updated underwriting).

- Enforceable collateral and credit support: Commercial loans commonly include a deed of trust on the property plus guarantees (personal and/or from related entities) and financial reporting covenants that continue through maturity and any extension.

What the Statutes Say

- N.C. Gen. Stat. § 45-36.24 (Expiration of lien of security instrument) – Defines how a secured obligation’s maturity date is determined for lien-expiration purposes and provides methods to extend a recorded lien’s maturity/expiration by recording certain documents.

- N.C. Gen. Stat. § 24-1.1 (Contract rates and fees) – Allows parties to contract for any agreed interest rate on loans over $25,000 and permits certain bank fees for modification, renewal, extension, or amendment (subject to limits stated in the statute).

Analysis

Apply the Rule to the Facts: The scenario involves a bank-financed commercial purchase with a long amortization and a shorter balloon/maturity period. That structure usually means the monthly payment is not the full story; the note’s maturity date controls when the remaining balance must be paid. If the plan is to keep the property beyond the balloon date, the practical path is to (1) negotiate an extension/renewal with the existing lender or (2) refinance with a new lender well before maturity, typically with updated financials and property information and, often, ongoing guarantees.

Process & Timing

- Who files: No one “files” to make the balloon go away; the borrower and lender negotiate. Where: The bank’s commercial lending department (and, if documents affecting the deed of trust are signed, the county Register of Deeds where the deed of trust is recorded). What: Typically a loan extension agreement, renewal/modification agreement, or a new loan closing (refinance). When: Commonly started 90–180 days before the maturity date, because underwriting, appraisals, and document drafting take time.

- Underwriting refresh: Many banks treat an extension like a new credit decision. Common requests include updated rent roll and leases (if applicable), operating statements, bank statements, entity documents, personal financial statement(s), tax returns, and proof of insurance. If the property is owner-occupied, the lender may also request information showing the operating business can support the debt service.

- Document and title steps: If the lender extends or modifies terms, the parties may sign documents that amend the note and may also amend, restate, or otherwise address the deed of trust. If a refinance occurs, the old loan is paid off at closing and the new lender records a new deed of trust.

Exceptions & Pitfalls

- Assuming an “automatic extension” exists: Some notes have an extension option, but many do not. Even when an option exists, it often requires strict notice, no existing defaults, and payment of an extension fee.

- Waiting too long to refinance: Appraisals, environmental diligence (when required), and entity/guarantor review can slow the process. A late start can force a rushed extension request or a distressed sale.

- Guarantee and entity structure surprises: Buying through a separate property-holding entity can help separate operations from real estate, but lenders often still require personal guarantees and may require cross-entity guarantees depending on cash flow and risk. Relatedly, transfers into or between entities can trigger “due-on-sale/due-on-transfer” or consent requirements in many loan documents.

- Owner-occupancy and use requirements: “Owner-occupied” is usually a lender underwriting category, not a single statewide rule. Banks may require the operating business to occupy a certain portion of the building and may underwrite based on business financials rather than (or in addition to) tenant income.

- Document mismatch: The amortization schedule, maturity date, default provisions, and any renewal language must align across the note, loan agreement, and deed of trust. Inconsistencies can create avoidable disputes at maturity.

For more background on related issues that often come up in the same transaction, see discussions of buying through a separate property-holding company, commercial loan personal guarantees, and common underwriting documents for self-employed borrowers.

Conclusion

In North Carolina, a balloon commercial real estate loan typically requires monthly payments based on a long amortization, but the remaining balance becomes due at the note’s stated maturity date unless the lender agrees in writing to extend, renew, or modify the loan. The practical way to handle maturity is to plan early for either a refinance or a negotiated extension. The most important next step is to review the promissory note for the maturity date and any extension conditions and start the lender conversation well before that date.

Talk to a Real Estate Attorney

If you’re dealing with a commercial loan that has a balloon maturity date and questions about refinancing, extensions, guarantees, or entity structure, our firm has experienced attorneys who can help you understand your options and timelines. Call us today at [919-341-7055].

Disclaimer: This article provides general information about North Carolina law based on the single question stated above. It is not legal advice for your specific situation and does not create an attorney-client relationship. Laws, procedures, and local practice can change and may vary by county. If you have a deadline, act promptly and speak with a licensed North Carolina attorney.